Project Management Estimating Case Study

Some people believe the primary critical factor for project success is the quality of the estimate. Unfortunately, not all companies have estimating databases, nor do all companies have good estimates. Some companies are successful estimating at the top levels of the work breakdown structure, while others are willing to spend the time and money estimating at the lower levels of the work breakdown structure.

In organizations that are project-driven and survive on competitive bidding, good estimates are often “massaged” and then changed based on the belief by management that the job cannot be won without a lower bid. This built-in process can and does severely impact the project manager’s ability to get people to be dedicated to the project’s financial baseline.

Capital Industries

In the summer of 2006, Capital Industries undertook a material development program to see if a hard plastic bumper could be developed for medium-sized cars. By January 2007, Project Bumper (as it was called by management) had developed a material that endured all preliminary laboratory testing.

One more step was required before full-scale laboratory testing: a three dimensional stress analysis on bumper impact collisions. The decision to perform the stress analysis was the result of a concern on the part of the technical community that the bumper might not perform correctly under certain conditions. The cost of the analysis would require corporate funding over and above the original estimates. Since the current costs were identical to what was budgeted, the additional funding was a necessity.

Frank Allen, the project engineer in the Bumper Project Office, was assigned control of the stress analysis. Frank met with the functional manager of the engineering analysis section to discuss the assignment of personnel to the task.

Functional manager: “I’m going to assign Paul Troy to this project. He’s a new man with a Ph.D. in structural analysis. I’m sure he’ll do well.”

Frank Allen: “This is a priority project. We need seasoned veterans, not new people, regardless of whether or not they have Ph.D.s. Why not use some other project as a testing ground for your new employee?”

Functional manager: “You project people must accept part of the responsibility for on-the-job training. I might agree with you if we were talking about blue-collar workers on an assembly line. But this is a college graduate, coming to us with a good technical background.”

Frank Allen: “He may have a good background, but he has no experience. He needs supervision. This is a one-man task. The responsibility will be yours if he fouls up.”

Functional manager: “I’ve already given him our book for cost estimates. I’m sure he’ll do fine. I’ll keep in close communication with him during the project.” Frank Allen met with Paul Troy to get an estimate for the job.

Paul Troy: “I estimate that 800 hours will be required.”

Frank Allen: “Your estimate seems low. Most three-dimensional analyses require at least 1,000 hours. Why is your number so low?”

Paul Troy: “Three-dimensional analysis? I thought that it would be a two dimensional analysis. But no difference; the procedures are the same. I can handle it.”

Frank Allen: “O.K. I’ll give you 1,100 hours. But if you overrun it, we’ll both be sorry.”

Frank Allen followed the project closely. By the time the costs were 50 percent completed, performance was only 40 percent. A cost overrun seemed inevitable. The functional manager still asserted that he was tracking the job and that the difficulties were a result of the new material properties. His section had never worked with materials like these before.

Six months later Troy announced that the work would be completed in one week, two months later than planned. The two-month delay caused major problems in facility and equipment utilization. Project Bumper was still paying for employees who were “waiting” to begin full-scale testing.

On Monday mornings, the project office would receive the weekly labor monitor report for the previous week. This week the report indicated that the publications and graphics art department had spent over 200 man-hours (last week) in preparation of the final report. Frank Allen was furious. He called a meeting with Paul Troy and the functional manager.

Frank Allen: “Who told you to prepare a formal report? All we wanted was a go or no-go decision as to structural failure.”

Paul Troy: “I don’t turn in any work unless it’s professional. This report will be documented as a masterpiece.”

Frank Allen: “Your 50 percent cost overrun will also be a masterpiece. I guess your estimating was a little off!”

Paul Troy: “Well, this was the first time that I had performed a three-dimensional stress analysis. And what’s the big deal? I got the job done, didn’t I?”

Polyproducts Incorporated

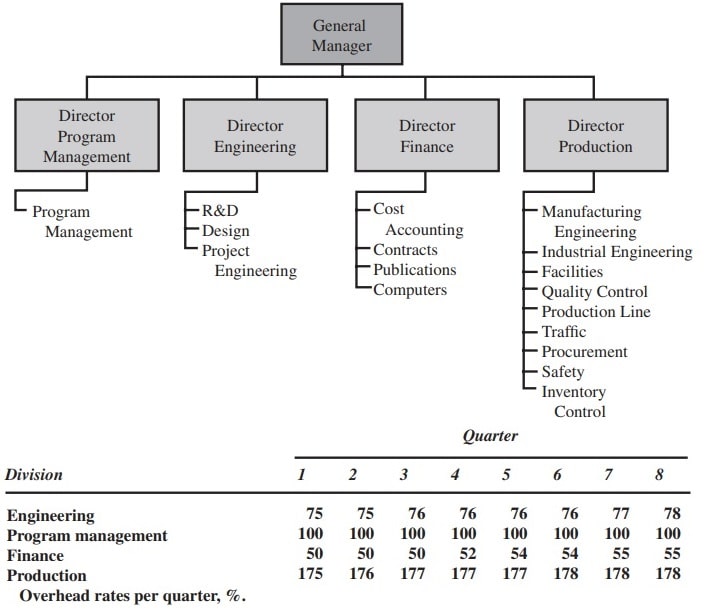

Polyproducts Incorporated, a major producer of rubber components, employs 800 people and is organized with a matrix structure. Exhibit I shows the salary structure for the company, and Exhibit II identifies the overhead rate projections for the next two years.

Polyproducts has been very successful at maintaining its current business base with approximately 10 percent overtime. Both exempt and nonexempt employees are paid overtime at the rate of time and a half. All overtime hours are burdened at an overhead rate of 30 percent.

On April 16, Polyproducts received a request for proposal from Capital Corporation (see Exhibit III). Polyproducts had an established policy for competitive bidding. First, they would analyze the marketplace to see whether it would be advantageous for them to compete. This task was normally assigned to the marketing group (which operated on overhead). If the marketing group responded favorably, then Polyproducts would go through the necessary pricing procedures to determine a bid price.

On April 24, the marketing group displayed a prospectus on the four companies that would most likely be competing with Polyproducts for the Capital contract. This is shown in Exhibit IV.

Exhibit I. Salary structure

Pay Scale

- 00

- 00

- 00

- 00

- 00

- 00

- 00

- 00

- 00

Number of Employees per Grade

|

Department 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

Total |

|

R&D |

5 |

40 |

20 |

10 |

12 |

8 |

5 |

100 | |

|

Design |

3 |

5 |

40 |

30 |

10 |

10 |

2 |

100 | |

|

Project engineering |

30 |

15 |

10 |

5 |

60 | ||||

|

Project management |

10 |

10 |

10 |

30 | |||||

|

Cost accounting |

20 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

60 | |||

|

Contracts |

3 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

10 | ||||

|

Publications |

3 |

5 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

20 | ||

|

Computers |

2 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

1 |

10 | |||

|

Manufacturing engineering |

2 |

7 |

7 |

3 |

1 |

20 | |||

|

Industrial engineering |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

10 | ||||

|

Facilities |

8 |

9 |

10 |

7 |

1 |

35 | |||

|

Quality control |

3 |

4 |

5 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

20 | ||

|

Production line |

55 |

50 |

50 |

30 |

10 |

5 |

200 | ||

|

Traffic |

2 |

2 |

1 |

5 | |||||

|

Procurement |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

10 | ||

|

Safety |

2 |

2 |

1 |

5 | |||||

|

Inventory control |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

10 |

At the same time, top management of Polyproducts made the following projections concerning the future business over the next eighteen months:

- Salary increases would be given to all employees at the beginning of the thirteenth month.

- If the Capital contract was won, then the overhead rates would go down 0.5 percent each quarter (assuming no strike by employees).

- There was a possibility that the union would go out on strike if the salary increases were not satisfactory. Based on previous experience, the strike would last between one and two months. It was possible that, due to union demands, the overhead rates would increase by 1 percent per quarter for each quarter after the strike (due to increased fringe benefit packages).

Exhibit II. Overhead structure

- With the current work force, the new project would probably have to be doneon overtime. (At least 75 percent of all man-hours were estimated to be performed on overtime). The alternative would be to hire additional employees.

- All materials could be obtained from one vendor. It can be assumed that rawmaterials cost $200/unit (without scrap factors) and that these raw materials are new to Polyproducts.

On May 1, Roger Henning was selected by Jim Grimm, the director of project management, to head the project.

Grimm: “Roger, we’ve got a problem on this one. When you determine your final bid, see if you can account for the fact that we may lose our union. I’m not sure exactly how that will impact our bid. I’ll leave that up to you. All I know is that a lot of our people are getting unhappy with the union. See what numbers you can generate.”

Exhibit III. Request for proposal

Capital Corporation is seeking bids for 10,000 rubber components that must be manufactured according to specifications supplied by the customer. The contractor will be given sufficient flexibility for material selection and testing provided that all testing include latest developments in technology. All material selection and testing must be within specifications. All vendors selected by the contractor must be (1) certified as a vendor for continuous procurement (follow-on contracts will not be considered until program completion), and (2) operating with a quality control program that is acceptable to both the customer and contractor.

The following timetable must be adhered to:

|

Month after Go-ahead |

Description |

|

2 4 5 9 13 17 18 |

R&D completed and preliminary design meeting held Qualification completed and final design review meeting held Production setup completed Delivery of 3,000 units Delivery of 3,500 units Delivery of 3,500 units Final report and cost summary |

The contract will be firm-fixed-price and the contractor can develop his own work breakdown structure on final approval by the customer.

Henning: “I’ve read the RFP and have a question about inventory control. Should I look at quantity discount buying for raw materials?”

Grimm: “Yes. But be careful about your assumptions. I want to know all of the assumptions you make.”

Henning: “How stable is our business base over the next eighteen months?”

Grimm: “You had better consider both an increase and a decrease of 10 percent. Get me the costs for all cases. Incidentally, the grapevine says that there might be follow on contracts if we perform well. You know what that means.”

Henning: “Okay. I get the costs for each case and then we’ll determine what our best bid will be.”

On May 15, Roger Henning received a memo from the pricing department summing up the base case man-hour estimates. (This is shown in Exhibits V and VI.) Now Roger Henning wondered what people he could obtain from the functional departments and what would be a reasonable bid to make.

Exhibit IV. Prospectus

|

Growth Rate | ||||||||

|

Business |

Last | |||||||

|

Base $ |

Year |

Profit |

R&D |

Contracts |

Number of |

Overtime Personnel | ||

|

Company |

Million |

(%) |

% |

Personnel |

In-House |

Employees |

(%) |

Turnover (%) |

|

Alpha |

10 |

10 |

5 |

Below avg. |

6 |

30 |

5 |

1.0 |

|

Beta |

20 |

10 |

7 |

Above avg. |

15 |

250 |

30 |

0.25 |

|

Gamma |

50 |

10 |

15 |

Avg. |

4 |

550 |

20 |

0.50 |

|

Polyproducts |

100 |

15 |

10 |

Avg. |

30 |

800 |

10 |

1.0 |

Exhibit V

To: Roger Henning From: Pricing Department Subject: Rubber Components Production

- All man-hours in the Exhibit (14–12) are based upon performance standards for a grade-7 employee. For each grade below 7, add 10 percent of the grade-7 standard and subtract 10 percent of the grade standard for each employee above grade 7. This applies to all departments as long as they are direct labor hours (i.e., not administrative support as in project 1).

- Time duration is fixed at 18 months.

- Each production run normally requires four months. The company has enough raw materials on hand for R&D, but must allow two months lead time for purchases that would be needed for a production run. Unfortunately, the vendors cannot commit large purchases, but will commit to monthly deliveries up to a maximum of 1,000 units of raw materials per month. Furthermore, the vendors will guarantee a fixed cost of $200 per raw material unit during the first 12 months of the project only. Material escalation factors are expected at month 13 due to renegotiation of the United Rubber Workers contracts.

- Use the following work breakdown structure:

Program: Rubber Components Production

Project 1: Support

TASK 1: Project office

TASK 2: Functional support

Project 2: Preproduction

TASK 1: R&D

TASK 2: Qualification

Project 3: Production

TASK 1: Setup

TASK 2: Production

Exhibit VI. Program: Rubber components production

|

Project Task |

Department |

Month | ||||||||||||||||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 | |||

|

1 |

1 |

Proj. Mgt. |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

480 |

|

1 |

2 |

R&D |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

|

Proj. Eng. |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 | ||

|

Cost Acct. |

80 |

80 |

80 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 | ||

|

Contracts |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 | ||

|

Manu. Eng. |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 | ||

|

Quality Cont. |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 | ||

|

Production |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 | ||

|

Procurement |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 | ||

|

Publications |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 | ||

|

Invent. Cont. |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 |

80 | ||

|

2 |

1 |

R&D |

480 |

480 | ||||||||||||||||

|

Proj. Eng. |

160 |

160 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Manu. Eng. |

160 |

160 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

2 |

2 |

R&D |

80 |

80 | ||||||||||||||||

|

Proj. Eng. |

160 |

160 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Manu. Eng. |

160 |

160 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Ind. Eng. |

40 |

40 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Facilities |

20 |

20 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Quality Cont. |

160 |

160 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Production |

600 |

600 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

Safety |

20 |

20 | ||||||||||||||||||

|

3 |

1 |

Proj. Eng. |

160 | |||||||||||||||||

|

Manu. Eng. |

160 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Facilities |

80 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Quality Cont. |

160 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

Production |

320 | |||||||||||||||||||

|

3 |

2 |

Proj. Eng. |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 |

160 | |||||

|

Manu. Eng. |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 | |||||||

|

Quality Cont. |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 |

320 | |||||||

|

Production |

1600 |

1600 |

1600 |

1600 |

1600 |

1600 |

1600 |

1600 |

1600 |

1600 |

1600 |

1600 |

1600 | |||||||

|

Safety |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 | |||||||

Small Project Cost Estimating at Percy

Company

Paul graduated from college in June 2000 with a degree in industrial engineering. He accepted a job as a manufacturing engineer in the Manufacturing Division of Percy Company. His prime responsibility was performing estimates for the Manufacturing Division. Each estimate was then given to the appropriate project office for consideration. The estimation procedure history had shown the estimates to be valid.

In 2005, Paul was promoted to project engineer. His prime responsibility was the coordination of all estimates for work to be completed by all of the divisions. For one full year Paul went by the book and did not do any estimating except for project office personnel manager. After all, he was now in the project management division, which contained job descriptions including such words as “coordinating and integrating.”

In 2006, Paul was transferred to small program project management. This was a new organization designed to perform low-cost projects. The problem was that these projects could not withstand the expenses needed for formal divisional cost estimates. For five projects, Paul’s estimates were “right on the money.” But the sixth project incurred a cost overrun of $20,000 in the Manufacturing Division.

In November 2007, a meeting was called to resolve the question of “Why did the overrun occur?” The attendees included the general manager, all division managers and directors, the project manager, and Paul. Paul now began to worry about what he should say in his defense.

Cory Electric

“Frankly speaking, Jeff, I didn’t think that we would stand a chance in winning this $20 million program. I was really surprised when they said that they’d like to accept our bid and begin contract negotiations. As chief contract administrator, you’ll head up the negotiating team,” remarked Gus Bell, vice president and general manager of Cory Electric. “You have two weeks to prepare your data and line up your team. I want to see you when you’re ready to go.”

Jeff Stokes was chief contract negotiator for Cory Electric, a $250-million-ayear electrical components manufacturer serving virtually every major U.S. industry. Cory Electric had a well-established matrix structure that had withstood fifteen years of testing. Job casting standards were well established, but did include some “fat” upon the discretion of the functional manager.

Two weeks later, Jeff met with Gus Bell to discuss the negotiation process:

Gus Bell: “Have you selected an appropriate team? You had better make sure that you’re covered on all sides.”

Jeff: “There will be four, plus myself, at the negotiating table; the program manager, the chief project engineer who developed the engineering labor package; the chief manufacturing engineer who developed the production labor package; and a pricing specialist who has been on the proposal since the kickoff meeting. We have a strong team and should be able to handle any questions.”

Gus Bell: “Okay, I’ll take your word for it. I have my own checklist for contract negotiations. I want you to come back with a guaranteed fee of $1.6 million for our stockholders. Have you worked out the possible situations based on the negotiated costs?”

Jeff: “Yes! Our minimum position is $20 million plus an 8 percent profit. Of course, this profit percentage will vary depending on the negotiated cost. We can bid the program at a $15 million cost; that’s $5 million below our target, and still book a $1.6 million profit by overrunning the cost-plus-incentive-fee contract. Here is a list of the possible cases.” (See Exhibit I.)

Gus Bell: “If we negotiate a cost overrun fee, make sure that cost accounting knows about it. I don’t want the total fee to be booked as profit if we’re going to need it later to cover the overrun. Can we justify our overhead rates, general and administrative costs, and our salary structure?”

Jeff: “That’s a problem. You know that 20 percent of our business comes from Mitre Corporation. If they fail to renew our contract for another two-year follow-on effort, then our overhead rates will jump drastically. Which overhead rates should I use?”

Gus Bell: “Let’s put in a renegotiation clause to protect us against a drastic change in our business base. Make sure that the customer understands that as part of the terms and conditions. Are there any unusual terms and conditions?”

Exhibit I. Cost positions

|

Negotiated |

Negotiated Fee | |||||

|

Target |

Overrun |

Total | ||||

|

Cost |

% |

Fee |

Fee |

Total Fee |

Package | |

|

15,000,000 |

14.00 |

1,600,000 |

500,000 |

2,100,000 |

17,100,000 | |

|

16,000,000 |

12.50 |

1,600,000 |

400,000 |

2,000,000 |

18,000,000 | |

|

17,000,000 |

11.18 |

1,600,000 |

300,000 |

1,900,000 |

18,900,000 | |

|

18,000,000 |

10.00 |

1,600,000 |

200,000 |

1,800,000 |

19,800,000 | |

|

19,000,000 |

8.95 |

1,600,000 |

100,000 |

1,700,000 |

20,700,000 | |

|

20,000,000 |

8.00 |

1,600,000 |

0 |

1,600,000 |

21,600,000 | |

|

21,000,000 |

7.14 |

1,600,000 |

–100,000 |

1,500,000 |

*22,500,000 | |

|

22,000,000 |

6.36 |

1,600,000 |

–200,000 |

1,400,000 |

23,400,000 | |

|

23,000,000 |

5.65 |

1,600,000 |

–300,000 |

1,300,000 |

24,300,000 | |

|

24,000,000 5.00 1,600,000 Assume total cost will be spent: 21,000,000 7.61 22,000,000 7.27 Minimum position = $20,000,000 |

–400,000 |

1,200,000 |

25,200,000 | |||

|

23,000,000 |

6.96 Minimum fee = 1,600,000 = 8% of minimum position | |||||

|

24,000,000 |

6.67 Sharing ratio = 90%/10% | |||||

Jeff: “I’ve read over all terms and conditions, and so have all of the project office personnel as well as the key functional managers. The only major item is that the customer wants us to qualify some new vendors as sources for raw material procurement. We have included in the package the cost of qualifying two new raw material suppliers.”

Gus Bell: “Where are the weak points in our proposal? I’m sure we have some.”

Jeff: “Last month, the customer sent in a fact-finding team to go over all of our labor justifications. The impression that I get from our people is that we’re covered all the way around. The only major problem might be where we’ll be performing on our learning curve. We put into the proposal a 45 percent learning curve efficiency. The customer has indicated that we should be up around 50 to 55 percent efficiency, based on our previous contracts with him. Unfortunately, those contracts the customer referred to were four years old. Several of the employees who worked on those programs have left the company. Others are assigned to ongoing projects here at Cory. I estimate that we could put together about 10 percent of the people we used previously. That learning curve percentage will be a big point for disagreements. We finished off the previous programs with the customer at a 35 percent learning curve position. I don’t see how they can expect us to be smarter, given these circumstances.”

Gus Bell: “If that’s the only weakness, then we’re in good shape. It sounds like we have a foolproof audit trail. That’s good! What’s your negotiation sequence going to be?”

Jeff: “I’d like to negotiate the bottom line only, but that’s a dream. We’ll probably negotiate the raw materials, the man-hours and the learning curve, the overhead rate, and, finally, the profit percentage. Hopefully, we can do it in that order.”

Gus Bell: “Do you think that we’ll be able to negotiate a cost above our minimum position?”

Jeff: “Our proposal was for $22.2 million. I don’t foresee any problem that will prevent us from coming out ahead of the minimum position. The 5 percent change in learning curve efficiency amounts to approximately $1 million. We should be well covered.

“The first move will be up to them. I expect that they’ll come in with an offer of $18 to $19 million. Using the binary chop procedure, that’ll give us our guaranteed minimum position.”

Gus Bell: “Do you know the guys who you’ll be negotiating with?”

Jeff: “Yes, I’ve dealt with them before. The last time, the negotiations took three days. I think we both got what we wanted. I expect this one to go just as smoothly.”

Gus Bell: “Okay, Jeff. I’m convinced we’re prepared for negotiations. Have a good trip.”

The negotiations began at 9:00 A.M. on Monday morning. The customer countered the original proposal of $22.2 million with an offer of $15 million.

After six solid hours of arguments, Jeff and his team adjourned. Jeff immediately called Gus Bell at Cory Electric:

Jeff: “Their counteroffer to our bid is absurd. They’ve asked us to make a counteroffer to their offer. We can’t do that. The instant we give them a counteroffer, we are in fact giving credibility to their absurd bid. Now, they’re claiming that, if we don’t give them a counteroffer, then we’re not bargaining in good faith. I think we’re in trouble.”

Gus Bell: “Has the customer done their homework to justify their bid?”

Jeff: “Yes. Very well. Tomorrow we’re going to discuss every element of the proposal, task by task. Unless something drastically changes in their position within the next day or two, contract negotiations will probably take up to a month.”

Gus Bell: “Perhaps this is one program that should be negotiated at the top levels of management. Find out if the person that you’re negotiating with reports to a vice president and general manager, as you do. If not, break off contract negotiations until the customer gives us someone at your level. We’ll negotiate this at my level, if necessary.”

Camden Construction Corporation

“For five years I’ve heard nothing but flimsy excuses from you people as to why the competition was beating us out in the downtown industrial building construction business,” remarked Joseph Camden, president. “Excuses, excuses, excuses; that’s all I ever hear! Only 15 percent of our business over the past five years has been in this area, and virtually all of that was with our established customers. Our growth rate is terrible. Everyone seems to just barely outbid us. Maybe our bidding process leaves something to be desired. If you three vice presidents don’t come up with the answers then we’ll have three positions to fill by midyear.

“We have a proposal request coming in next week, and I want to win it. Do you guys understand that?”

BACKGROUND

Camden Construction Corporation matured from a $1 million to a $26 million construction company between 1989 and 1999. Camden’s strength was in its ability to work well with the customer. Its reputation for quality work far exceeded the local competitor’s reputation.

Most of Camden’s contracts in the early 1990s were with long-time customers who were willing to go sole-source procurement and pay the extra price for quality and service. With the recession of 1995, Camden found that, unless it penetrated the competitive bidding market, its business base would decline.

In 1996, Camden was “forced” to go union in order to bid government projects. Unionization drastically reduced Camden’s profit margin, but offered a greater promise for increased business. Camden had avoided the major downtown industrial construction market. But with the availability of multimillion-dollar skyscraper projects, Camden wanted its share of the pot of gold at the base of the rainbow.

MEETING OF THE MINDS

On January 17, 1999, the three vice presidents met to consider ways of improving Camden’s bidding technique.

V.P. finance: “You know, fellas, I hate to say it, but we haven’t done a good job in developing a bid. I don’t think that we’ve been paying enough attention to the competition. Now’s the time to begin.”

V.P. operations: “What we really need is a list of who our competitors have been on each project over the last five years. Perhaps we can find some bidding trends.”

V.P. engineering: “I think the big number we need is to find out the overhead rates of each of the companies. After all, union contracts specify the rate at which the employees will work. Therefore, except for the engineering design packages, all of the companies should be almost identical in direct labor man-hours and union labor wages for similar jobs.”

V.P. finance: “I think I can hunt down past bids by our competitors. Many of them are in public records. That’ll get us started.”

V.P. operations: “What good will it do? The past is past. Why not just look toward the future?”

V.P. finance: “What we want to do is to maximize our chances for success and maximize profits at the same time. Unfortunately, these two cannot be met at the same time. We must find a compromise.”

V.P. engineering: “Do you think that the competition looks at our past bids?”

V.P. finance: “They’re stupid if they don’t. What we have to do is to determine their target profit and target cost. I know many of the competitors personally and have a good feel for what their target profits are. We’ll have to assume that their target direct costs equals ours; otherwise we will have a difficult time making a comparison.”

V.P. engineering: “What can we do to help you?”

V.P. Finance: “You’ll have to tell me how long it takes to develop the engineering design packages, and how our personnel in engineering design stack up against the Reviewing the Data

Exhibit I. Proposal data summary (cost in tens of thousands)

|

Year |

Acme |

Ajax |

Pioneer |

Camden Bid |

Camden Cost |

|

1990 |

270 |

244 |

260 |

283 |

260 |

|

1990 |

260 |

250 |

233 |

243 |

220 |

|

1990 |

355 |

340 |

280 |

355 |

300 |

|

1991 |

836 |

830 |

838 |

866 |

800 |

|

1991 |

300 |

288 |

286 |

281 |

240 |

|

1991 |

570 |

560 |

540 |

547 |

500 |

|

1992 |

240* |

375 |

378 |

362 |

322 |

|

1992 |

100* |

190 |

180 |

188 |

160 |

|

1992 |

880 |

874 |

883 |

866 |

800 |

|

1993 |

410 |

318 |

320 |

312 |

280 |

|

1993 |

220 |

170 |

182 |

175 |

151 |

|

1993 |

400 |

300 |

307 |

316 |

283 |

|

1994 |

408 |

300* |

433 |

449 |

400 |

|

1995 |

338 |

330 |

342 |

333 |

300 |

|

1995 |

817 |

808 |

800 |

811 |

700 |

|

1995 |

886 |

884 |

880 |

904 |

800 |

|

1996 |

384 |

385 |

380 |

376 |

325 |

|

1996 |

140 |

148 |

158 |

153 |

130 |

|

1997 |

197 |

193 |

188 |

200 |

165 |

|

1997 |

750 |

763 |

760 |

744 |

640 |

*Buy-in contracts

competition’s salary structure. See if you can make some contacts and find out how much money the competition put into some of their proposals for engineering design activities. That’ll be a big help.

“We’ll also need good estimates from engineering and operations for this new project we’re suppose to bid. Let me pull my data together, and we’ll meet again in two days, if that’s all right with you two.”

REVIEWING THE DATA

The executives met two days later to review the data. The vice president for finance presented the data on the three most likely competitors (see Exhibit I). These companies were Ajax, Acme, and Pioneer. The vice president for finance made the following comments:

- In 1993, Acme was contract-rich and had a difficult time staffing all of its projects.

- In 1990, Pioneer was in danger of bankruptcy. It was estimated that it neededto win one or two in order to hold its organization together.

- Two of the 1992 companies were probably buy-ins based on the potential forfollow-on work.

- The 1994 contract was for an advanced state-of-the-art project. It is estimatedthat Ajax bought in so that it could break into a new field.

The vice presidents for engineering and operations presented data indicating that the total project cost (fully burdened) was approximately $5 million. “Well,” thought the vice president of finance, “I wonder what we should bid so it we will have at least a reasonable chance of winning the contract?”

The Estimating Problem

Barbara just received the good news: She was assigned as the project manager for a project that her company won as part of competitive bidding. Whenever a request for proposal (RFP) comes into Barbara’s company, a committee composed mainly of senior managers reviews the RFP. If the decision is made to bid on the job, the RFP is turned over to the Proposal Department. Part of the Proposal Department is an estimating group that is responsible for estimating all work. If the estimating group has no previous history concerning some of the deliverables or work packages and is unsure about the time and cost for the work, the estimating team will then ask the functional managers for assistance with estimating.

Project managers like Barbara do not often participate in the bidding process. Usually, their first knowledge about the project comes after the contract is awarded to their company and they are assigned as the project manager. Some project managers are highly optimistic and trust the estimates that were submitted in the bid implicitly unless, of course, a significant span of time has elapsed between the date of submittal of the proposal and the final contract award date. Barbara, however, is somewhat pessimistic. She believes that accepting the estimates as they were submitted in the proposal is like playing Russian roulette. As such, Barbara prefers to review the estimates.

One of the most critical work packages in the project was estimated at twelve weeks using one grade 7 employee full time. Barbara had performed this task on previous projects and it required one person full time for fourteen weeks. Barbara asked the

©2010 by Harold Kerzner. Reproduced by permission. All rights reserved.

estimating group how they arrived at this estimate. The estimating group responded that they used the three-point estimate where the optimistic time was four weeks, the most likely time was thirteen weeks, and the pessimistic time was sixteen weeks.

Barbara believed that the three-point estimate was way off of the mark. The only way that this work package could ever be completed in four weeks would be for a very small project nowhere near the complexity of Barbara’s project. Therefore, the estimating group was not considering any complexity factors when using the three-point estimate. Had the estimating group used the triangular distribution where each of the three estimates had an equal likelihood of occurrence, the final estimate would have been thirteen weeks. This was closer to the fourteen weeks that Barbara thought the work package would take. While a difference of 1 week seems small, it could have a serious impact on Barbara’s project and incur penalties for late delivery.

Barbara was now still confused and decided to talk to Peter, the employee that was assigned to do this task. Barbara had worked with Peter on previous projects. Peter was a grade 9 employee and considered to be an expert in this work package. As part of the discussions with Barbara, Peter made the following comments:

I have seen estimating data bases that include this type of work package and they all estimate the work package at about 14 weeks. I do not understand why our estimating group prefers to use the three point estimate.

“Does the typical data base account for project complexity when considering the estimates?” asked Barbara. Peter responded:

Some data bases have techniques for considering complexity, but mostly they just assume an average complexity level. When complexity is important, as it is in our project, analogy estimating would be better. Using analogy estimating and comparing the complexity of the work package on this project to the similar works packages I have completed, I would say that 16–17 weeks is closer to reality, and let’s hope I do not get removed from the project to put out a fire somewhere else in the company. That would be terrible. It is impossible for me to get it done in 12 weeks. And adding more people to this work package will not shorten the schedule. It may even make it worse.

Barbara then asked Peter one more question:

Peter, you are a grade 9 and considered as the subject matter expert. If a grade 7 had been assigned, as the estimating group had said, how long would it have taken the grade 7 to do the job?

“Probably about 20 weeks or so” responded Peter.

QUESTIONS

- How many different estimating techniques were discussed in the case?

- If each estimate is different, how does a project manager decide that one estimateis better than another?

- If you were the project manager, which estimate would you use?

The Singapore 1 Software Group (A)

BACKGROUND

The Singapore Software Group (SSG) was a medium-sized company that had undergone significant growth over the past twenty years. Initially, the company provided software services just to the Pacific Rim countries. Now, they serviced all of Asia and had contracts and partnerships with companies in Europe, South America, and North America.

SSG’s strengths were in software development, database management, and management information systems. SSG created an excellent niche for itself and maintained a low-risk strategy whereby growth was funded out of cash flow rather than through bank borrowing. The low-risk strategy forced SSG to focus on providing the same type of high-quality deliverables to its existing and new clients rather than expanding into other software development markets with other products and services. While SSG had a reputation for quality products and services, excellence in customer support, and competitive pricing, the software landscape was changing.

SSG had seen a 400 percent increase in the number of small companies entering the marketplace over the past several years and competing with them in

1©2010 by Harold Kerzner. Reproduced by permission. All rights reserved. This case study is fictitious.

Need for Growth

their core lines of business. Its client base was under attack by other Southeast Asian countries that had lower salary structures and a lower cost of living, thus allowing these new companies to put pressure on SSG’s profit margins.

Under the direction of senior management, SSG performed a SWOT

(strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) analysis. SSG’s strengths were quite clear: highly talented and dedicated personnel; a fairly young labor force; and significant knowledge related to its existing products and services. Its internal weaknesses were also quite apparent; while SSG provided training and educational opportunities to its workforce, it was limited to educational programs that would directly support existing products and services only; for the business to expand, significant expenses would be incurred for retraining its labor force or workers with new talents would need to be hired; and last, the time necessary to expand the business may take too long.

The threats to SSG were real. SSG did not know if it could maintain its current growth rate. SSG had already seen signs that its growth rate may be deteriorating since many of its critical clients were now seeking out competitors that possessed skills that SSG did not have. There was no question that the opportunities for growth existed if SSG could expand its skills in a timely manner and penetrate new fields. The question, of course was “What new skills do we need? ” and “What new products can we offer? ” There were opportunities for joint ventures and partnerships, but SSG preferred to remain independent, and often with a go-it-alone mentality.

NEED FOR GROWTH

In a bold move, SSG began training its work force in the type of software development necessary to support the i-phone, i-pad, and other screen interfacing software packages. Although SSG had some rather limited experience in this area, software to support touch screens was seen as the future. This included software to support games, telecommunications, photography, and videotaping.

SSG realized that training alone would not be sufficient. Time was a real serious constraint for the plans for continued growth. It would be necessary to hire additional staff with expertise in computer engineering rather than just computer programming. SSG was fortunate to be able to attract highly talented people with the expertise needed to compete in this area. Some of the new hirers even came from SSG’s competitors that were looking at opportunities to enter this marketplace. It took almost a year and significant expense to build the in-house skills that SSG desperately needed for future growth. With some in-house experimental work, SSG was able to eliminate many of the software “bugs” that plagued the first-generation touch-screen products and even exceeded performance in some cases. But all this was just part of educational development and limited R&D.

What was needed now were contracts.

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) FROM TAIWAN TECHNOLOGIES

Taiwan Technologies (TT) was one of SSG’s most important clients. SSG was on TT’s preferred supplier list and was awarded more contracts from TT than from any other client. Many of the contracts were awarded on points, including past performance, rather than simply being the lowest bidder.

TT was in the process of designing new products to enter the smart phone marketplace and compete with other smart phones suppliers. TT’s major strengths were in redesigning someone else’s products and improving the performance and quality. Without having to recover vast R&D costs that others were incurring, TT was able to become a low-cost supplier. TT’s strengths were manufacturing-driven and it possessed very limited capability in software development.

SSG was one of five companies invited to bid on creating the software. The problem was that TT’s design efforts were still in progress and SSG’s efforts would be done in parallel with TT’s work in progress. TT’s specifications were only partially complete. The final designs would not be known until perhaps six months into the project.

To complicate matters further, TT was requiring that the contract be a firmfixed-price effort. Usually, parallel development work is done with cost-reimbursable contracts. With a firm-fixed-price contract, SSG could be exposed to significant risks, especially if downstream scope changes resulted in rework. The risks could be partially mitigated through a formalized change control process. Since the number and magnitude of the downstream scope changes were unknown, having the project manager on board the project on a full-time basis was critical.

PROPOSAL KICKOFF MEETING

SSG’s senior management made an immediate decision that SSG would be bidding on this contract. In attendance at the bidding kickoff meeting were senior representatives from all of the groups that would be supplying support for the project. Also in attendance was the chief executive officer (CEO) who announced that Jim Kirby would be the project manager and would be assigned full time for the duration of the project. The project manager would be expected to work 2000 hours of direct labor.

Frank Ling (Business Analyst): “As the business analyst, it is my responsibility to make sure that we have the right business case for this project. The following information in the business case is critical for project planning:

- The market demand for the TT products could be millions of units a year.

- Downstream product upgrades will provide SSG with a long term cash flow stream.

- SSG views this project as an essential component of our strategic plan.

- The project may require some technological breakthroughs and, as yet, we are unsure what these breakthroughs might be. However, we feel confident that we can do it in a timely manner.

- Even though we have people trained in this technology, this is a completely new type of project for SSG. We know there are risks.

- Corporate legal says that TT’s product requirements thus far pose no legal headaches for SSG.

We expect that the business case may change until such time as TT finalizes their product description and requirements. In this regard, I will be working closely with Jim Kirby on the impact that the changes will have on the business case and the project. Parallel development projects are always difficult.

SSG’s interest in winning this bid is of the utmost importance, but we do not want to win it at a price that is so low that we are losing money. We need to know as soon as possible what the realistic cost is to meet their requirements. The successful completion of this contract will ’open doors’ for us elsewhere. ”

Kathryn James (VP, Human Resources): “According to the RFP, the goahead date is July 1st, 2011 and a completion date of June 30th, 2012. At SSG, we typically evaluate people for promotion in [the] first two weeks of December, and the promotions go into effect the beginning of January. We also provide costof-living adjustments and salary increases the first week of January as well. We expect that the average cost-of-living and salary adjustment to be 6% beginning January 1st. For those who receive promotions, they will receive an additional 10% salary increase on average.

There are other facts that must be considered since the program is a year in length. Last year, the average person in the company had:

- Three weeks of paid vacation

- 10 paid holidays

- 4 days of paid sick leave

- 5 days of training paid by corporate 2 days of jury duty

These costs are paid out of corporate overhead and are not part of direct labor.

I am also providing you with the salary structure for the departments that are expected to provide support for the project. (See Exhibit I.) If[B1] overtime is required, and I assume it will be, all workers will be paid at time and a half, regardless of pay grade.

The overhead rates for each of the departments are also included in Exhibit I. However, on overtime, the overhead rates are only 50% of the overhead rates on regular time. ”

Exhibit I Salary information for 2011

|

Department |

Pay Grade |

2011 Median Hourly Salary, $ |

Overhead, % |

|

Project Manager |

9 |

56 |

100 |

|

Systems Programmer |

5 |

38 |

150 |

|

Systems Programmer |

6 |

41 |

150 |

|

Systems Programmer |

7 |

45 |

150 |

|

Systems Programmer |

8 |

49 |

150 |

|

Software Programmer |

5 |

38 |

150 |

|

Software Programmer |

6 |

41 |

150 |

|

Software Programmer |

7 |

45 |

150 |

|

Software Programmer |

8 |

49 |

150 |

|

Software Engineer |

6 |

41 |

150 |

|

Software Engineer |

7 |

45 |

150 |

|

Software Engineer |

8 |

49 |

150 |

|

Software Engineer |

9 |

55 |

150 |

|

Manufacturing Engineer |

6 |

41 |

250 |

|

Manufacturing Engineer |

7 |

45 |

250 |

|

Manufacturing Engineer |

8 |

49 |

250 |

|

Manufacturing Engineer |

9 |

55 |

250 |

Paul Creighton (Chief Financial Officer, CFO): “Kathryn has provided you with the overhead rates for our departments. We expect these overhead rates to remain the same for the duration of the project. Also, our corporate general and administrative costs (G&A) will remain fixed at 8%. The G&A cost are included in all of our contracts and are a necessity to support corporate headquarters. This contract is a firm-fixed-price effort which you all know provides significant risk to the seller. To mitigate some of our possible risk, I want a 15% profit margin included in the contract. In the past, the contract profit margins on TT contracts ranged from 10% to 15%. The higher end of the range was always on the firmfixed-price contracts.

I know this is the first time we have worked on a contract like this and that there are risks. I am not opposed to adding in a management reserve as protection. But before you go overboard in adding in a large management reserve, just remember that we want to win the contract. ”

Ellen Pang (VP, Computer Technologies): “I consider this project to be at the top of the priority list for SSG. Therefore, we will assign the appropriate resources with the necessary skill levels to get the job done. I will assign five people full time for the duration of the project; one from systems programming, three from software programming, and one from software engineering. I believe that each employee will be required to work at least 2000 hours of direct labor on this project, with the hours broken down equally each month.

I am not sure right now which employees I will assign because the go-ahead date is a few months away. But I will keep my promise that there will be five workers, and that they will be committed full time with no responsibilities on other projects. In addition, I am hiring a consultant with expertise in this type of project. The cost for the consultant for the duration of the project will be $75,000. ”

Eric Tong (VP, Manufacturing): “I’m sure you all know from newspapers and TV news broadcasts about the problems smart phone manufacturers were having with the casing and cover. To avoid having the same problems and alienating TT, I will be assigning one of my manufacturing engineers who is an expert in value engineering and quality. I expect him to be assigned for roughly 600 hours beginning some time after January, 2012.

The RFP requires that we experiment with various size touch screens to see if the software is affected by the screen size and screen thickness. This could be part of the problem that other suppliers were having. This experimental work is also included as part of the manufacturing engineer’s job.

I estimate that we will need about $6000 in material costs. We should probably include a scrap factor as well, but I am unsure right now how much of a scrap factor is reasonable. ”

Bruce Clay (Proposal Manager): “TT wants the proposal in their hands within 30 days. I think that’s enough time . . . to make our estimates. Here is a copy of a small proposal we did for TT a couple of years ago. (See Exhibit II.) It should give you an idea how we price out our projects for competitive bidding.

Together with your individual estimates, I also need a listing of all of the assumptions you made in arriving at your estimate(s). This is critical information for risk management and decisions on scope changes. ”

Exhibit II.Typical project pricing summary

|

Dept. |

Hours |

Rate |

Dollars % |

Dollars |

Total |

|

Eng. |

1000 |

$42.00 |

$42,000 110 |

$46,200 |

$88,200 |

|

Manu. |

500 |

$35.00 |

$17,500 200 |

$35,000 |

$52,500 |

|

Total Labor |

$140,700 | ||||

|

Other: Subcontracts $10,000 Consultants $ 2,000 |

$12,000 | ||||

|

Total Labor and material: |

$152,700 | ||||

|

Corporate G & A: 10% |

$ 15,270 $167,970 | ||||

|

Profit: 15% |

$ 25,196 $193,166 | ||||

The Singapore 2 Software Group (B)

DETERMINING WHAT TO BID

You and your team have carefully reviewed the risks and the associated costs. It is pretty obvious that there is quite a bit of risk exposure on this project. Had the RFP stated that the contract would be cost-reimbursable, your exposure to risks might be less.

The decision made by your team is to recommend to senior management that a 15 percent management reserve be added into the contract and to submit a bid price of $2,279,762. You present your recommendations to senior management for review and approval. Your company has a policy that any bids over $500,000 have to be reviewed and approved by an executive committee. You tell senior management about your concerns over the risks and request that they contact TT to see if the contract type could be changed to a cost-reimbursable contract type.

Your CEO informs you and your team that he has good working relations with TT because of all of the previous contracts SSG did for them. The CEO then states:

Taiwan Technologies has no intention of changing the contract type. I already asked them about this, and they will not make any changes to the solicitation package. Furthermore, I have been informed from reliable sources that they have committed only $1.5 million for this contract and are pretty sure that they will get bidders at this price.

The CEO then asks you to go back to the drawing board, sharpen your pencil, and see what financial risks SSG would be exposed to if SSG submitted a bid of $1.5 million.

The Singapore 3 Software Group (C)

MANAGEMENT’S DECISION

You and your team have carefully reviewed costs and present your findings to management. You are surprised by the fact that management actually seems pleased that the loss would be only $106,780. Obviously, management has been thinking about this for some time, but you did not know about it.

Management tells you that they are willing to submit a bid of $1.5 million to TT. The CEO looks over your pricing sheet and says:

We need a pricing sheet that gets us to exactly $1.5 million on price. Work backwards to generate the numbers. I want the pricing sheet to show a profit of $170,000. Leave in the scrap factor on materials, but eliminate the consultant. We will pay for the consultant’s time using another source of internal funds, but do not identify him on this proposal. Also, eliminate the overtime hours and overtime costs. And for simplicity sake, just give us a total burdened labor cost rather than breaking it down by department.

©2010 by Harold Kerzner. Reproduced by permission. All rights reserved.

The Singapore 4 Software Group (D)

ANOTHER CRITICAL DECISION

As always, management was correct. You submitted a bid of $1.5 million and were awarded the contract. Work has been taking place as planned. There have been some scope changes, but they had only a minor impact on the cost and schedule thus far.

By the end of the eighth month of the project, your team makes a hardware and software breakthrough that may revolutionize touch-screen technology. You are pretty sure that none of TT’s competitors have this technology and that TT will certainly capture a large portion of the marketplace when its products are introduced. The new technology could be applied to laptops and PCs as well.

SSG believes that this new technology can generate a significant cash flow stream for years to come. However, there is a serious problem. Because the contract is a firm-fixed-price effort, the intellectual property rights are owned by TT. SSG has limited usage of the technology and cannot license it to other companies.

You present your concerns to management. A week later, you and your team are asked to appear before the senior management committee. The CEO says:

I have explained our position to Taiwan Technologies. They have agreed to allow use to change the contract type from firm-fixed-price to cost-sharing. In the cost-sharing contract, the profit is removed from consideration and SSG will pay 40% of all costs and TT will pay the remaining 60% of the costs up to a maximum of 60% of the total cost line in the proposal. This is a win-win situation for both parties. Furthermore, TT will allow SSG to have shared intellectual property right but only after TT’s products have been in the marketplace for 90 days.

The CEO then asks you to recalculate your numbers and see how much money SSG had to pay out-of-pocket to develop this technology, including the cost of the consultant.

To Bid 1 or Not to Bid

BACKGROUND

Marvin was the president and chief executive officer (CEO) of his company. The decision of whether or not to bid on a job above a certain dollar value rested entirely upon his shoulders. In the past, his company would bid on all jobs that were a good fit with his company’s strategic objectives and the company’s win-to-loss ratio was excellent. But to bid on this job would be difficult. The client was requesting certain information in the request for proposal (RFP) that Marvin did not want to release. If Marvin did not comply with the requirements of the RFP, his company’s bid would be considered as nonresponsive.

BIDDING PROCESS

Marvin’s company was highly successful at winning contracts through competitive bidding. The company was project-driven and all of the revenue that came into the company came through winning contracts. Almost all of the clients provided the company with long-term contracts as well as follow-on contracts.

New RFP

Almost all of the contracts were firm-fixed-price contracts. Business was certainly good, at least up until now.

Marvin established a policy whereby 5 percent of sales would be used for responding to RFPs. This was referred to as a bid-and-proposal (B&P) budget. The cost for bidding on contracts was quite high and clients knew that requiring the company to spend a great deal of money bidding on a job might force a no-bid on the job. That could eventually hurt the industry by reducing the number of bidders in the marketplace.

Marvin’s company used parametric and analogy estimating on all contracts. This allowed Marvin’s people to estimate the work at level 1 or level 2 of the work breakdown structure (WBS). From a financial perspective, this was the most cost-effective way to bid on a project knowing full well that there were risks with the accuracy of the estimates at these levels of the WBS. But over the years continuous improvements to the company’s estimating process reduced much of the uncertainty in the estimates.

NEW RFP

One of Marvin’s most important clients announced it would be going out for bids for a potential ten-year contract. This contract was larger than any other contract that Marvin’s company had ever received and could provide an excellent cash flow stream for ten years or even longer. Winning the contract was essential.

Because most of the previous contracts were firm-fixed-price, only summary-level pricing at the top two levels of the WBS was provided in the proposal. That was usually sufficient for the company’s clients to evaluate the cost portion of the bid.

The RFP was finally released. For this project, the contract type would be cost-reimbursable. A WBS created by the client was included in the RFP, and the WBS was broken down into five levels. Each bidder had to provide pricing information for each work package in the WBS. By doing this, the client could compare the cost of each work package from each bidder. The client would then be comparing apples and apples from each bidder rather than apples and oranges. To make matters worse, each bidder had to agree to use the WBS created by the client during project execution and to report costs according to the WBS.

Marvin saw the risks right away. If Marvin decided to bid on the job, the company would be releasing its detailed cost structure to the client. All costs would then be clearly exposed to the client. If Marvin were to bid on this project, releasing the detailed cost information could have a serious impact on future bids even if the contracts in the future were firm-fixed-price.

TO BID OR NOT TO BID

Marvin convened a team composed of his senior officers. During the discussions which followed, the team identified the pros and cons of bidding on the job:

- Pros:

- A lucrative ten-year (or longer) contract

- The ability to have the client treat Marvin’s company as a strategic partner rather than just a supplier

- Possibly lower profit margins on this and other future contracts but greater overall profits and earnings per share because of the larger business base

- Establishment of a workable standard for winning more large contracts

- Cons:

- Release of the company’s cost structure

- Risk that competitors will see the cost structure and hire away some of the company’s talented people by offering them more pay

- Inability to compete on price and having entire cost structure exposed could be a limiting factor on future bids

- If the company does not bid on this job, the company could be removed from the client’s bidder list

- Clients must force Marvin’s company to accept lower profit margins

Marvin then asked the team, “Should we bid on the job?”

QUESTIONS

- What other factors should Marvin and his team consider?

- Should they bid on the job?